Beginning on January 1, 2016, I have sent a postcard each day to a friend documenting the date, the time I got out of bed, my location, and the number of days that I have lived to that point. This project arose from the intersection of three recent experiences which have given me a heightened sense of time, its unfailing and eternal passing, and the finite moments that remain to me in this lifetime.

The first event was the passing of my college roommate and dear friend, Jeff Shields in August, 2014—the fourth close friend from Harvard who has died since we were all young, capped-and-gowned college graduates. The second experience has been an increasing fascination with Conceptual Art, in part through Susan’s and my interest and visits to the Herb and Dorothy Vogel 50×50 collections in museums all across the country and in part through my own interest and experience in this art form. Since I don’t have the skills to paint, sculpt, photograph, etc, my conceptual art projects have been focused on an obsessive completion of a conceptual challenge (e.g. my 3.5 mile hikes up Rowe Hill behind our home in Vermont on every day of the calendar, a project that took about 9 years and was completed on December 10, 2013.) The third experience and the one that was the proximate stimulus for the postcards was becoming acquainted with the conceptual art of On Kawara through an exhibit at the Guggenheim Museum in the spring of 2015 and then a close reading of the catalogue for that show.

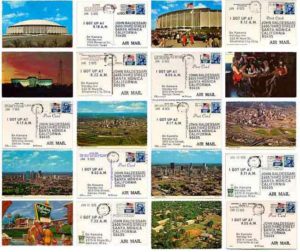

Kawara was a Japanese born artist who lived from 1934-2014, primarily in New York after 1965. His work is intensely (perhaps, insanely) focused on time, its passing, its dailiness, its finiteness for each individual, and the paradox of our wish to treasure each moment in the face of the sameness of the quotidian, making most days forgettable and unremarkable. Kawara addressed this paradox through a number of clever and challenging approaches. His most famous work, “Today”, consists of over 3000 Day paintings, single color backgrounds on which the date has been painted in his own invented font. These paintings with a subtitle on the back side were housed in individual boxes lined with clippings from that day’s newspaper. If Kawara failed to finish his painting by midnight, he destroyed it. Perhaps even more fascinating are his four integrated projects carried out over a 12 year period from May 12, 1968 to September 17, 1979 (coincidentally, my 34th birthday). On every day of those 12 years, he sent two postcards to friends (“I GOT UP”), traced his movements on a map (“I WENT”), recorded encounters with individuals (“I MET”), and cut out newspaper articles of interest (“I READ”). The maps, lists of people, and newspaper articles were meticulously recorded in journals. Kawara also painted 100 year calendars and created a series of bound journals with pages listing the one million years before 1970 and the one million years after 1980, providing the basis for performance art in which a man and a woman alternate reading the years in a public performance, perhaps most notably in Trafalgar Square over five days in 2004. Another work involved sending more than 900 telegrams over a 30 year period to various friends, artists, gallery owners, etc with a single message: “I AM STILL ALIVE”.

Kawara’s daily record of the coordinates of space and time, totally separated from any personal details of his life, serves as a minimalist encounter with the elapsing of the artist’s existence. The artless acts of sending postcards and recording daily activities when carried out to this vast extent is both absurd and sublime. As one essayist in the catalogue says: “Is a date banal or monumental? Or is this in itself a banal dichotomy; instead, do the dates by which we measure our lives appear in the vast territory between the unmarked and the significant? In the minor epiphany, the involuntary memory, the coincidence, the secret or shared meaning, do we find the actual density of human temporal experience? “

In summary (and with apologies for the length of this explanation), I am sending a postcard every day as a way of marking the days of my life in recognition that they are limited and as a way to pause and take an action that imbues each day with at least some small significance. The message on the card simply indicates that I am here and you are there, and we are both still blessedly alive. The card provides the proof that life is lived one day at a time, and the sum of those days is inevitably less than we want. It’s an attempt to move beyond the sameness of the daily and inject a creative act into each and every day—to make each day different and special in some small way.