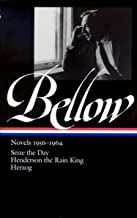

Herzog, Saul Bellow 1961

OY VEY! Poor Moses Elkanah Herzog! Through 416 densely packed pages, Bellow floods the reader with Herzog’s tsouris and madness. A 47 year old Professor (of what, I’m not sure but probably literary criticism, though history or philosophy are also possibilities) who is twice divorced and estranged from his former wives, father of two, living in NY but with roots in Chicago, owner of a rambling mansion in the Berkshires, and with $600 in his bank account, Herzog endlessly processes his failures, his disastrous relationships, his family history, his unfinished manuscript, his love life with the florist Ramona, his anger at his lawyer, his doctor, his psychiatrist, his former wives, and on and on. In the final pages, alone and unwell in his Berkshire house, his internal dialogue (represented throughout the book in italicized harangues) turns to himself as he says/thinks: “But what do you want, Herzog?” A perfect summary of the book, a classic tale of male, mid-life confusion and fear. Life has not given Herzog what he expected, growing up in his family of three boys and a sister, moving from Canada to Chicago, getting his PhD, marrying and having children. Instead, he is confused and frightened as professional and personal failure, impotency, loneliness and old age await. “Still, he need only know his own mind.” he thinks but that is exactly what Herzog proves unable to do. Bellow, the winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1976, the Pulitzer and three National Book Awards, demonstrates his skills as a prolific and profound writer in this, perhaps his best known novel. It’s not an easy book to get through, but the virtuoso performance of Bellow makes it worth the time and effort. Bellow moved from Chicago to Brookline, MA where he co-taught a course with James Wood who wrote this eulogy in the New Republic:

I judged all modern prose by his. Unfair, certainly, because he made even the fleet-footed—the Updikes, the DeLillos, the Roths—seem like monopodes. Yet what else could I do? I discovered Saul Bellow’s prose in my late teens, and henceforth, the relationship had the quality of a love affair about which one could not keep silent. Over the last week, much has been said about Bellow’s prose, and most of the praise—perhaps because it has been overwhelmingly by men—has tended toward the robust: We hear about Bellow’s mixing of high and low registers, his Melvillean cadences jostling the jivey Yiddish rhythms, the great teeming democracy of the big novels, the crooks and frauds and intellectuals who loudly people the brilliant sensorium of the fiction. All of this is true enough; John Cheever, in his journals, lamented that, alongside Bellow’s fiction, his stories seemed like mere suburban splinters. Ian McEwan wisely suggested last week that British writers and critics may have been attracted to Bellow precisely because he kept alive a Dickensian amplitude now lacking in the English novel. … But nobody mentioned the beauty of this writing, its music, its high lyricism, its firm but luxurious pleasure in language itself. … [I]n truth, I could not thank him enough when he was alive, and I cannot now.