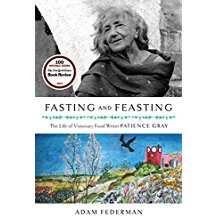

Fasting and Feasting: The Life of Visionary Food Writer Patience Gray, Adam Federman 2017

I read this book because it was one of the seven finalists for this year’s Vermont Book Award, a $5000 annual prize given by the Vermont College of Fine Arts and because I intended to review all seven of the books for my Bennington Banner column. After a few dozen pages, I began to regret that decision, bogged down in details of the life of an obscure, dead English woman. However, by the time I closed the book at its 304th page, I had become thoroughly enthralled with Patience, an independent and creative woman who was a thought leader and active participant in the ‘back to nature’ movement of the 1970’s and in the food revolution that has brought us real, slow, and healthy food. Gray (b. 1917-d.2006) was born Patience Stanham, the middle girl of a conventional upper middle class British family (though there was a secret great-grandfather who had been a rabbi in Europe) but soon showed her willingness to set her own course. She traveled widely in Europe as a young woman and had a multi-year affair in her 20’s that resulted in three children and her last name before ending it. She was deeply connected with the world of design and writing, editing the woman’s column for the Observer and designing wallpaper patterns. She published her first cookbook (Plats du Jour) to some acclaim in 1957. Her life changed forever the next year when she met Norman Mommens, a Dutch sculptor living in England. Mommens left his wife and stepson, and along with Gray spent the rest of their lives in creative pursuits in a series of ever more primitive and distant locations including Naxos, Greece and finally, an 11 acre abandoned property in Puglia, Italy called Spigolizzi where they lived from 1968 until Norman’s death in 2000 and Patience’s in 2006. Mommens’ sculpture was displayed at the Venice Biennale and in various London galleries and Gray’s five books including the ground-breaking Honey From a Weed are concrete evidence of their productivity and creativity, but perhaps more important were the relationships Gray had with other ‘foodies’ leading the way in cooking and eating simply and depending on the plants and fungi that grow locally. Federman has done a remarkable job of scholarship evidently based on interviews and his reading of the voluminous correspondence which Gray conducted throughout her life with a variety of fascinating individuals. This is not a book that everyone will find engaging, but I did. It’s a good reminder that some of the most fascinating people in the world are not seeking power, wealth, and prestige, but are living everyday according to their beliefs and finding new ways of expressing those.