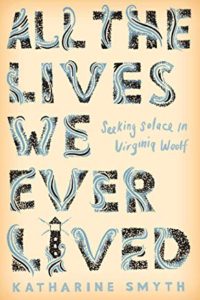

All the Lives We Ever Lived: Seeking Solace in Virginia Woolf, Katharine Smyth 2019

Smyth’s father died at 59 in 2007, and deeply grieving, she found solace in writing about him in the context of her relationship with Virginia Woolf. Woolf’s life and her work, especially “To the Lighthouse” not only provided comfort to Smyth but also provided the framework for a beautiful and thought-provoking book about life, death, loss, and marriage. Beginning with her parents’ marriage of 30 years and drawing heavily on the real life marriages of Virginia and Leonard Woolf, Virginia’s parents, Julia Duckworth and Leslie Stephens, and the marriage of Mr. and Mrs. Ramsay in “To the Lighthouse”, Smyth explores the complexity and uniqueness of each marriage, what she refers to as the ‘idiosyncratic, often unwieldy bonds we forge in wedlock, and as yet another reminder that, in marriage as in life, nothing is simply one thing.’ Smyth had her own personal experience to draw upon, as well, since her five year long marriage dissolved one night when her husband simply left while she was sleeping never to be seen again. The author, an only child, was clearly deeply attached to her father, a situation that I found myself constantly wondering about since her father was an alcoholic, a failed architect and businessman despite his Harvard Business School degree, and a smoker who continued to abuse his body even after diagnosed with kidney and bladder cancer. The interweaving of the Woolfs, the Ramsays, and the Smyths is brilliantly done, and there are wonderful phrases and paragraphs of beauty and wisdom throughout the book. Smyth tries desperately to understand her father and herself—-‘this present self could occlude the selves that came before’, and the contradictory notion that we are, in fact, as the title suggests ‘all the lives we ever lived‘ that the ‘power of the past to erase us, to steal from us every last moment of which are lives are composed’. This notion of the past and its hold upon us and the opposite notion that everything disappears as time moves on is the central tension of the book. How do we hold on to someone who has died? How do we relive the joy of past moments? In one extra-ordinary paragraph she quotes Mrs. Ramsay’s musings on immortality: “that community of feeling with other people which emotion gives as if the walls of partition had become so thin that practically (the feeling was one of relief and happiness) it was all one stream, and chairs, tables, maps, were hers, were theirs, it did not matter whose, and Paul and Minta would carry it out when she was dead.” Smyth goes on to write, “How curious, how compelling, this vision of the dissolution of the boundaries between people, so that it all—our houses, our belongings, our selves—becomes eternal; passes from us to our friends, to their friends, to their friends; a single steady river that will forever flow.” What a fascinating and comforting notion that our presence, our places, even ourselves in some sense live on forever in the ongoing human family. Like Woolf who was powerfully attached to place and family (Talland in Cornwall, the house in South Kensington in London, The Monk’s House in Sussex) Smyth is also strongly attached to place—-the houses in Charlestown and the Rhode Island shore which her father rebuilt. The title clearly states that Smyth found solace in Virginia Woolf who had also experienced great loss (her mother, then her father, her step-sister, and then her brother) and especially in “To the Lighthouse” where Lily, the spinsterish painter who can’t quite seem to finish her picture, survives Mrs. Ramsay, Pru who dies in childbirth, and Andrew who dies in WWI. Loss is everywhere but Smyth perseveres through memory and literature.