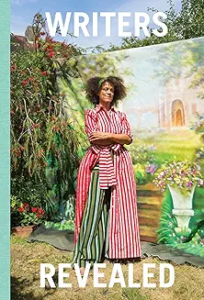

Writers Revealed: Treasures from the British Library and the National Portrait Gallery by Catherine MacLeod and Alexandra Ault 2025

What a fascinating concept these two curators have realized in “Writers Revealed: Treasures from the British Library and the National Portrait Gallery”. The latter is our favorite museum in London, one which we visit several times during our month long stay each March while I don’t believe I’ve ever been in the British Library.

The two curators set out to “tell the stories of some of the best-loved writers in the English language casting light on their enduring appeal from the 16th C to today through the collections of the British Library and the National Portrait Gallery.” Featuring original manuscripts, letters, and notebooks from the Library’s collection paired with portraits, photographs, drawings and other depictions of the writer from the National Portrait Gallery’s collection, the brief bios of each of the 72 authors from Shakespeare and Ben Jonson in the 17th C to Zadie Smith and several other contemporary authors provide fascinating details and little known factoids.

The book is not perfect. One bothersome element was the manner in which the authors organized the chapters. Instead of going with chronology or even subject matter (e.g. poetry vs novels), they chose five rather obscure themes—In Search of the Author, The Journey to Success, Suppression, Censorship and Secrecy, Fame, and Writing to Change the World. As a result, a chapter on Rudyard Kipling was followed by one on Harold Pinter, strange bedfellows to say the least; in another strange juxtapostion, Arthur Conan Doyle was followed by the Indian Nobel Prize winner, Rabindranath Tagore, whom I had never heard of to my embarassment.

I also found the seemingly endless use of “greatest writer of the x century” to be annoying and unnecessary. Dickens, George Eliot, the Brontes, Auden, and others all qualify for that appellation, but labelling each one was repititous and annoying. Inclusion should have been enough to ensure their value.

A final quibble was that each and every name in the text including publishers, reviewers, critics, etc was followed by the birth and death dates in parentheses. This proved distracting at best and annoying at worst. These could easily have been elminated making the reading experience easier and more pleasant.

One interesting and surprising set of writers were Jamaican, Nigerian, and Indian authors who while resisting colonialism and slavery, were nonetheless thoroughly British. I’d never heard of Hanif Kureishi, Aphra Behn, C.L.R. James, Andrew Salkey, Mervyn Peake, Sam Selvin, John La Rose, George Lamming, Ignatius Sancho, Olaudah Equiano, Una Marson, Linton Kwesi Johnson, or Benjamin Zephaniah before. It’s one big world and learning about these authors has been fascinating for this Western-oriented, English-only speaking reader!

This is not a book to be read straight through. It would be like drinking from a fire hose, but keeping it nearby on the bedside table and dipping into it from time to time will provide you with great enjoyment from reading the biographical information to looking at the original manuscript or letter and the portrait. Dickens as a young man; Rushdie as an Indian mystic; Shelly and Byron in all their sexual adventurous selves. A real treat!

While I have not quite forgiven them for omitting Robert Louis Stevenson, they did include someone I had never heard of, Mervyn Peake who illustrated the 1949 Eyre and Spottiswoode edition of ‘Treasure Island’ my childhood favorite. In addressing Peake’s illustrations, the authors referred to Long John Silver as the “captain of the Hispaniola” when, in fact, he was the ship’s cook. I sent an email to both MacLeod and Ault pointing out this error, and in typical British fasion, I heard back promptly from both of them acknowledging the error, promising to correct it in future editions, and thanking me for my attentive reading. Gotta love those Brits!