Walking by Henry David Thoreau 1851

During this month of reading about walking, I decided to re-read Thoreau’s classic essay on the topic. When I sat down to write this review, I discovered that I had read and reviewed this essay twice before, in 2016 and again only 9 months ago. Those reviews, one of which I’ve attached below had captured most of my observations on this, my third reading, but once again, I was impressed that a re-reading has the potential of discovering new elements in a familiar work.

In this re-reading, I was impressed by how closely Thoreau’s transcendental philosophy mirrored today’s Buddhist mindfulness teachings. Thoreau urges his reader to not dwell in the past with the remonstration that ‘Above all, we cannot afford not to live in the present.” Once you work through the double negative, it is clear that, like mindfulness, Thoreau is urging the reader to forget regrets and limit worry, to recognize that the past is gone and the future is so deeply contingent that it is futile to spend time worrying about it. This presentness, this being fully awake and in touch with the present moment, is central to Buddhism and clearly to Thoreau as well.

Another parallel which even uses the same words is the emphasis on the ‘beginner’s mind’ that is urged by the Buddhist teacher, Shuryu Suzuki in his book, “Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind”. Thoreau writes ‘A man’s ignorance sometimes is not only useful, but beautiful….My desire for knowledge is intermittent, but my desire to bathe my head in atmospheres unknown to my feet is perennial and constant. The highest that we can attain to is not Knowledge, but Sympathy with Intelligence.” Thoreau goes on to write about the ‘advantage of our actual ignorance.‘

Finally, Thoreau urges that the walker ‘get there in spirit…to forget all my morning occupations and my obligations to society…to shake off the village.’ He asks the question: “What business have I in the woods if I am thinking of something out of the woods?” This is an almost perfect restatement of the mindfulness direction to clear the mind and to not be distracted by random thoughts, regrets, worries.

It is perhaps no coincidence that while I was reading Thoreau I was also reading Thich Nhat Hanh’s book, “You Are Here”, one of his many works on mindfulness. Hanh and Thoreau would have enjoyed each other’s company—-the Vietnamese, Buddhist monk who has done so much to bring mindfulness practice to modern readers and the transcendental philosopher who felt that wildness was the preservation of the world and urged his readers to leave their desks, store counters, and commercial pursuits to lose themselves in Nature. Wise men, separated by nearly 200 years but sharing a common view of the good.

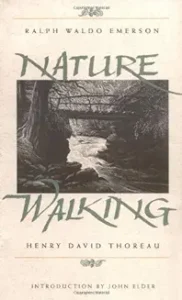

The second new impression I had upon re-reading this essay was the beauty of the etchings by Thomas Nason. Beginning with the beautiful scene of a bridge crossing a mountain stream in the forest and continuing throughout the volume, Nason’s engravings are quite wonderful and vividly evoked for me the Vermont countryside with its rolling hills, streams, and forests were I do my walking. The prints are all from the collection of the Boston Public Library which has an extensive holdings in Nason’s work. The artist was born in 1889 and died in 1971 and spent his adult life making prints of his native New England scenery. His work is held at the Smithsonian, the National Gallery of Art in DC, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Whitney, and other prominent museums, and it contributes wonderfully to this simple paperback volume published by Beacon.

Here, then, is my more recent review of Walking from 2023: