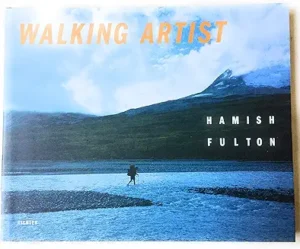

Walking Artist by Hamish Fulton 2001

This is the second book about Hamish Fulton loaned to me by Andrew Witkin of the Krakow-Witkin Gallery in Boston. The books were among the selections on the table during a recent exhibit that included several of Fulton’s photographs. Since I own two of Fulton’s prints and have enjoyed them for several years, I was eager to read more about him.

“Walking Artist”, published in 2001, differs from the 2002 Tate Britain Catalogue of his one-man exhibit in that it has more of Fulton and less from commentators. There is a fine interview with mountaineer Phil Bartlett and an excellent critical analysis by Angela Vettese, but the most informative writing is by Fulton himself. The book begins with several dense pages covered from top to bottom and left to right with Fulton’s words and phrases separated by solid red boxes. These are followed by five pages of uninterrupted sentences, phrases, or isolated words in black font with occasional red that serve as a stream of consciousness as Fulton considers his walks and his artwork. Phrases such as ‘one foot in front of the other’, ‘lost in thought’, “anytime, anywhere”, “where to begin, where to stop?” give the reader a sense of Fulton’s thinking. He also cites his major influences: Native American culture, Himalayan art, Western (US) mountaineers, and Japanese Haiku poets.

He goes on to write tht he walks the land in order to be ‘woven into nature’ and that he creates the artwork that memorializes the walks as an acknowledgment of time, the time of his life in relation to the sun, moon, and stars and out of respect for their existence. In addition, he identifies a 1973 walk of 1022 miles over 47 days from the ‘top to the bottom, Duncansby Head to Land’s End, Scotland, Wales, and England’ when he was 27 years old, as the moment when he made his commitment to only make art related to the experience of individual walks. His equation of time=life, life=art, art=walk, and walk=time sums it all up.

The photographs and word art are rather remarkable visually, but the reality is that it is the walks themselves that stagger the imagination. I counted 27 countries, states, or provinces which he walked in this collection, and that not a complete summary of his work by any means. The timing of nature—its solstices, phases of the moon, eclipses, nights, and days—and the ever-changing but ancient rocks, boulders, rivers, clouds are his companions and references. He cites ‘boulder time” and contrasts it with his own lifespan.

I loved this book, and I admire all of Fulton’s work, the walks and the art. I think you will as well. If you’re in Boston, visit the Krakow-Witkin gallery and hold the work in your own hands. You’ll be transported.