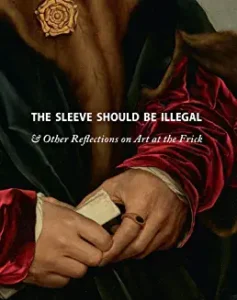

The Sleeve Should be Illegal & Other Reflections on Art at the Frick edited by Michaelyn Mitchell 2021

This book is thought-provoking, aesthetically pleasing, unusual in its approach, and quite successful in its presentation of one of America’s finest art collections, The Frick.

Henry Clay Frick (1849-1919) was a robber baron of extra-ordinary dimension. His investments in coke, steel, railroads, and real estate created vast wealth with which he purchased the Renaissance and Old Master works that comprise the collection. He left the Fifth Avenue building which had been the home for him and for the art collection to the public in his will. The building and its collection have continued to growin the centur y since his death while remaining true to its roots—no Jackson Pollacks or Alexander Calders here! The building is currently closed for its fourth major renovation.

The Collection’s goal is not to be all encompassing since it focuses on painting, sculpture, and the decorative arts from the 15th-19th C. In like fashion, this volume is not a comprehensive catalog but rather the individual and often idiosyncratic views and opinions of 62 contributors. I was frustrated by the lack of an explanation of how the process worked: how did the editor choose these 62 individuals and what was their assignment? It appears that each person was told to choose their favorite work in the collection and write a brief essay about it. The essays can be characterized as modern ‘ekphrasis’ which traditionally involved a poet writing lines about a work of art.

The contributors represent a wide array of individuals and backgrounds from philanthropists to artists and writers and singers and dancers. Mark Morris, Roz Chast, Bill T. Jones, Adam Gopnik (who also wrote the foreward), Lena Dunham (who provocatively drops the ‘f’ word into this otherwise rather staid set of observations), Daniel Mendelsohn, Jonathan Lethem (It is a line from his essay that was used for the strange but eye-catching title!) are among the contributors.

The pleasures of this wonderful volume include first and foremost the works of art. The most commented upon work is Rembrandt’s self portrait from 1658 followed closely by Bronzino’s 1550 painting of Lodovico Capponi and two of Vermeer’s gems. Tiepolo, Gainsborough, Turner, Velasquez, and other major figures come in for single essays. My personal favorites are the two portraits by Holbein that grace the sides of a huge fireplace in the Living Hall: Thomas Cromwell and Thomas More stare at each other with calm and steely hostility as they did as competitors in Henry VIII’s 16th C. court. Both ultimately lost the real counterparts to the beautifully rendered heads that fill these two frames.

Minor quibbles are that I disliked the font which was too fine and prissy for my aging eyes. Also, the decision to pair a photograph of only a portion of the work of art with each essay, often resulted in a failed search for a feature noted by the essayist. While each work is shown in its entirety in a much smaller format at the end of the book, the lack of congruence between the essay and the paired photo was frustrating.

That said, this is a fine book and a treat for any art lover. It’s also a testimony to the art of the essay and the importance of close observation, what one writer calls ‘the eyeling’ of a work of art. Over and over again, the commentators wonder at the ability of the artist to capture light, person, and life with paint, brush, and canvas. I can’t wait to visit the new Frick when it reopens and to once again, experience the close eyeling and the aesthetic frisson communicated by the contributors to this volume.