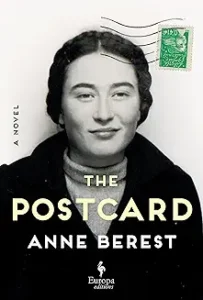

In general, I avoid reading novels or non-fiction books that focus on the Holocaust. I find it way too upsetting, unsettling, disturbing, and at the end of the process, nightmare producing. So when this book appeared in the NYT Sunday Book Review, my first impulse was to not even read the review, but the title grabbed me. In case you haven’t visited my web site at www.EpsteinReads.com, if you go there you will find a heading of ‘Other Projects’ and under that heading, there is a section on Postcards.

Inspired by the Japanese-American artist On Kawara, I began to send a daily postcard to friends and family on which I note the date, where I am writing from, what number postcard this is (today’s was #2880), what day of my life it is (today’s was 28,540) and what time I awoke (today it was 6:58, I slept in!). I also have been sending postcards every Monday to my four grandchildren. Simon has received 486 of them and Franny is now up to 109 with Lucy and Jonah in between. In other words, postcards are a large part of my life, so how could I avoid this book.

Well, I tried to, returning it to the Cambridge Public Library after reading 142 increasingly upsetting pages, but when several friends recommended it, I picked it up again, and I’m glad I did. It’s a very good book, but as predicted, I found the portion of the book where the Rabinovitch family were arrested, interned in France, and then sent under utterly unthinkable conditions to Auschwitz to be unbearably sad and disturbing. Auschwitz is where Ephraim and Emma and their 19 year old Naomi 17 year old Jacques were murdered. How could educated, cultured people possibly conceive of and carry out the Final Solution? How could their French neighbors, friends, and police help the Nazis???

The book’s conceit is built around the arrival of a postcard addressed to the one surviving member of the Rabinovitch family, Myriam. The year is 2003, and the postcard has nothing but the names of the four Rabinovitch’s who were murdered. The postcard has no return address and its arrival aunches a remarkable search for its source by Myriam’s daughter, Leila and her daughter, Anne. The history of the Rabinovitch family from Lodz, Poland to Palestine and finally to rural France is gradually filled in through the conversations between Leila and Anne, as they eventually solve the mystery of the postcard.

This is an excellent novel with a finely wrought plot and vivid characters. But, as I had predicted, it has left me with too vivid images of the murder of 6,000,000 Jews by the Nazis and their willing allies. Given today’s rise of anti-semitism on college campuses and in other settings, this book has only added to my anxiety and sleeplessness. There are several sentences and pages in the book, written in French several years ago, that are particularly poignant in today’s troubled world. At one point, a friend of Anne’s, Gerard, is telling her about an episode in his childhood when he asked his mother about the numbers tattooed on their friends’ arms. The mother explains that they are phone numbers inscribed there to help the elderly to remember them, but when Gerard as an adult reflects back to that time, he says “It’s better not to be Jewish in this world. It doesn’t make you a lesser being, but it doesn’t make you a greater one either.”

But perhaps the most painful passage in the book is one where Anne is trying to understand the anti-semitism that confronted her family throughout the 20th C, in Poland in 1925, in Paris in 1950, in 1985, and again in 2020. She says, “The pattern was undeniable. Something had to be learned from all these lives. But what? Reflection. Examination. A deeper questioning of that word whose definition remained elusive. What does it mean to be Jewish?”

Anne goes on to frame in her mind a response to a woman at a seder who asked her if she was ‘truly Jewish’. Anne says, “I don’t know what it means to be ‘truly Jewish’ or ‘not truly Jewish.’ All I can tell you is that I’m the child of a survivor. That is, someone who may not be familiar with the seder rituals, but whose family died in the gas chambers. Someone who has the same nightmares as her mother, and is trying to find her place among the living. Someone whose body is the grave of those who never had a proper burial. …So yes, it would suit me not to think about Auschwitz every day. It would suit me for things to be different. It would suit me not to be afraid of the government, afraid of gas, afraid of losing my identity papers, afraid of enclosed spaces, afraid of dog bites, afraid of crossing borders, afraid of traveling by airplane, afraid of crowds, and the glorification of virility, afraid of men in groups, afraid of my children being taken from me, afraid of people who obey orders, afraid of uniforms, afraid of being late, afraid of being stopped by the police, afraid whenever I have to renew my passport. Afraid of saying that I’m Jewish. I’m afraid of all those things, all the time. I carry within me, inscribed in the very cells of my body, the memory of an experience of danger so violent that sometimes I think I really lived it myself, or that I’ll be forced to relive it one day. To me, death always feels near. I have a sense of being hunted. I often feel subjected to a kind of self-obliteration. I search in the history books for the things I was never told. I can’t read enough; I always want to read. My hunger for knowledge is never sated, sometimes I feel like a stranger here. A foreigner. I see obstacles where others do not. I struggle endlessly to make a connection between the thought of my family and the mythologized occurance that is genocide. And that struggle is what constitutes me. It is the thing that defines me. I am the daughter and granddaughter of survivors.”

These sentences spoke loudly to me. Through good fortune and the fact that my grandparents left Europe well before WWII, I am not the child of survivors, but I’ve felt these same feelings though clearly to a much lesser extent. How could it have happened? How safe am I and my children and grandchildren as today’s world turns nauseatingly and steadily towards fascism and anti-semitism? Each of us has to decide how to read and live in these times, but this book helped me begin to make sense of this world.

Click here to add your own text