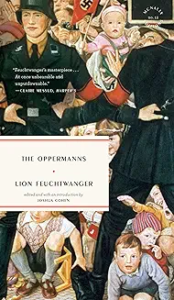

The Oppermanns by Lion Feuchtwanger 1933 (transl. 2022)

Feuchtwanger wrote “The Oppermanns” in 1933, the year that Hitler became Chancellor, the Reichstag was burned, and the campaign to murder Germany’s Jews moved from isolated pogroms to a state policy.

The book chronicles the destruction of the Oppermann family who had lived and thrived in Berlin for three generations and had been German citizens for over 300 years building businesses and professional careers, and fighting in WWI on the side of the Kaiser and their country. We meet Martin, who has continued to grow the furniture company that his grandfather had founded and made a household word throughout Germany. We meet Edgar, a famous surgeon who had developed a new operation to treat cancer patients in his own thriving clinic. We meet Gustav, a worldly and sophisticated bachelor whose daily routine involved horseback riding, exercises, and reading in his vast library, and we also meet their sister, Kate who is married to an American Jew whose citizenship status differentiates him from the rest of the family and their son, Berthold, who experiences a year of anti-semitic bullying from his National Socialist teacher.

The book, written in real time, provides a shattering first hand account of how Germany’s Jews were harassed and ultimately murdered by the Germans who had drunk Hitler’s Kool Aid while their neighbors and friends looked on or rather, looked away. Lies and more lies accompanied by violence, threats, and fear were the Nazis’ strategy (sound familiar?). As the book ends, we find Gustav has died after he decides that silence is not tolerable and intentionally returns to Germany. When he speaks out in a public setting against The Leader, he is arrested and spends months in a National Socialist concentration camp for disorderly conduct. Gustav is eventually freed through the intervention of Aryan friends but soon dies, a broken man. Edgar relocates to self-exile in Paris and Martin flees to England. Ruth, Edgar’s daughter, moves to Palestine. Bethold, Martin’s son is dead, a suicide triggered by the unremitting bullying of his teacher.

Much of what Feuchtwanger writes about Hitler as The Leader could easily apply to our own current autocrat. “Blockhead”, “lunatic”, “barbarian” all seem as appropriate in 2025 as they did in 1933. Here’s the businessman, Martin arguing with his family for calm and patience in the face of the growing Nazi threat: “I do not understand why all of you suddenly have the jitters.What has happened? A popular blockhead has been given an important office and has had a check put on him by the appointment of able men as his colleagues. Do you really believe that, because a few thousand young armed ruffians roam about in the streets, there is an end of Germany?”

But Martin was wrong. Within a few weeks of his calming words there were 3000 dead, 30,000 beaten and injured, and 100,000 dissidents, Jews, intellectuals imprisoned in the Storm Troopers’ concentration camps. Yes, it was the end of the Germany of Bach, Beethoven, Goethe. Ask that question of today’s America where an unpopular blockhead has surrounded himself with yes-men who are not capable and filled some of our cities, not with ruffians, but with military carrying automatic weapons and then ask yourself if that means the coming end of the U.S. of Washington, Jefferson, FDR, and Obama.

The book, for me, ultimately addressed the question of what does one do in the face of an immoral, anti-semitic, authoritarian government. If a Jew, do you stay or do you leave? If a Gentile, do you look away and keep quiet or speak out and push back? Gal Beckerman wrote in “The Atlantic” in December 2022: “Feuchtwanger himself doesn’t seem to be offering a template for how democracy dies. If anything, in his novel, templates shatter easily and quickly. For all the lessons he is trying to impart in 1933, there is no clearer answer about when exactly it’s time to go, when holding on to dignity becomes self-indulgent and dangerous. What remains instead is a deep sense of that rumbling “elemental force,” and the impossible choices should you find yourself stuck in its path.”

Feuchtwanger’s book is powerfu and important because of what it describes and when it was written. It sold more than 200,000 copies, was translated into 10 languages and yet it had no visible impact on the implacable steamroller that destroyed German democracy and the Jews of Europe. Pertinent today? For sure!