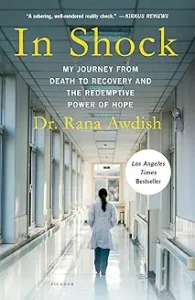

In Shock: My Journey From Death to Recovery and the Redemptive Power of Hope by Rana Awdish 2017

Rana Awdish was a young attending intensive care physician in the ICU’s at the prestigious Henry Ford Hospital when she suddenly became critically ill and moved abruptly from the white coated doctor making rounds at the bedside to the dying patient in the bed. She was seven months pregnant and presented to the Emergency Room with severe abdominal pain and shock. Taken emergently to the OR, she lost an enormous amount of blood into her abdomen from a hemorrhage from her liver and died on the operating room table, only to be resuscitated and launched into a year of hospitalizations, emergency surgeries, and other complications.

This is a tale of the miracles of modern medicine as well as the failures that accompany those miracles. Suffering from two benign liver tumors, one of which bled to start this seemingly endless cycle of severe illness, Awdish used her medical knowledge and sophistication to identify the barriers in communication which often interfere with the quality of care. Sometimes treated as if she were not awake and aware, she often heard her doctors using terms such as “she’s circling the drain” or “she’s trying to die on us” which provided the physicians emotional distance while estranging her, the patient.

The book ultimately is about how doctors are trained and how they interact with patients. Awdish decries the traditional advice to medical students and residents to ‘distance’ themselves from their patients and not get emotionally involved. One paragraph led me to tears as she described how an attending physician admonished her for crying at the bedside when a patient was dying. The attending physician’s advice that she ‘can’t help her other patients’ if she is emotionally disabled by the dying one was nearly identical to advice I was given when I was a junior resident at Boston Children’s caring for a nine year old boy dying of cystic fibrosis. It was poor advice in 1972, and it was poor advice when given to Awdish 50 years later.

Awdish takes her near death experience and years of living with serious medical problems and makes the plea for doctors to be kind to themselves as well as to their patients. By acknowledging the heartbreak, guilt, and sense of failure that is inevitable in caring for patients, many of whom will die despite our best efforts, doctors can become more resilient and better able to help their patients while helping themselves. Communication, openness, group support are all necessary if we are to avoid physician burnout and if we are going to provide the care patients yearn for and deserve.

Francis W. Peabody, a surgeon at MGH, in a lecture to medical students in 1927 said “Time, sympathy and understanding must be lavishly dispensed, but the reward is to be found in that personal bond which forms the greatest satisfaction of the practice of medicine. One of the essential qualities of the clinician is interest in humanity, for the secret of the care of the patient is in caring for the patient.” Awdish makes a compelling plea for this approach to those human beings who for reasons often obscure or unknown find themselves suddenly catapulted into the role of patient. Doctors owe it to each and every one of them to bring their best game every day to every patient.

My wife and I have annually given copies of a book to each entering Internal Medicine resident at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, a Harvard teaching hospital where I was a fellow and years later the Executive Vice President. After years of giving copies of Atul Gawande’s excellent book, “Being Mortal”, we gave “In Shock” to the residents this year. It’s message is important for them to think about as they transition from student to physician.