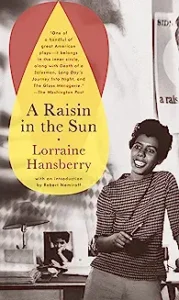

A Raisin in the Sun by Lorraine Hansberry 1959

Hansberry was only 29 when her first play was produced on Broadway in 1959, making her the youngest woman and the first African-American woman to bring a play to Broadway. When ‘A Raisin in the Sun’ went on to win the New York Drama Critics Circle Award, she and her play joined the pantheon of great 20th C theater along with ‘The Glass Menagerie’, ‘The Death of a Salesman’, and ‘Long Days Journey into Night’.

Hansberry died of pancreatic cancer in 1965 at the age of 34 during the Broadway run of her second play,’ The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window’, abruptly ending a brilliant career. Her legacy and much of her unpublished work was advanced by her husband Robert Nemiroff.

‘A Raisin in the Sun’ takes its title from a Langston Hughes poem, ‘Harlem’ which reads: “What happens to a dream deferred?/ Does it dry up like a raisin in the sun?/Or fester like a sore—/and then run? Does it stink like rotten meat?/Or crust and sugar over—/like a syrupy sweet?/ Maybe it just sags/like a heavy load./Or does it explode.”

Most references to this poem and Hansberry’s play only quote the first two lines of ‘Harlem’, but Hansberry’s play embraces all of the options, focusing on the alternatives for how a dream deferred will end up. The Younger family, Walter Jr., his wife Ruth and son Lucas, his sister Beneatha, and the elder of the family, his mother Lena reflect all of these alternatives as they struggle with poverty, discrimination and a world of pain while living on Chicago’s South Side in the 1950’s.

The ‘raisin in the sun’ motif flows through the entire play as Lena struggles to provide sun to her struggling house plant in an apartment where there is no light. Walter struggles with his dreams of being a wealthy man who can provide his wife with pearls and send his son to the best college. Beneatha’s suitor, Asagai, a Nigerian, struggles with the desire to end colonialism and bring independence to his nation, and Lena struggles to keep her family together and no longer defer their dreams.

I read this book after seeing the play performed in a small black box theater in Watertown, MA last week. I had seen it a number of years before in a downtown Boston theater, and the impact this time was much greater. Was it the intimacy of the theater, the power of the acting, or was it the accumulated frustration, grief, and sadness that seems to endlessly accumulate in our nation’s struggle for racial equality and understanding? Sadly, the play’s portrayal of Blacks trapped in dead end jobs, slum like housing, and lack of capital remains largely unchanged from when it was written 65 years ago.

The play featured Sidney Poitier, Lou Gossett and Ruby Dee when it premiered on Broadway and Danny Glover when it was produced for American Playhouse on TV in 1989. The performers in Watertown were not famous actors, but the power of the drama was in no way diminished. If you have the opportunity to see this American classic, by all means do so. If more people had seen it in 1959 and in the intervening years, perhaps we would not be experiencing the white backlash of today.