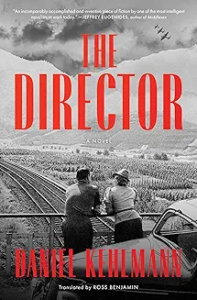

The Director by Daniel Kehlman 2023 (English translation 2025)

This powerful novel is based on the life of G.W. Pabst, a famous Austrian movie director in the early to mid 20th century who made films in Germany during the Third Reich.

Kehlner uses this Pabst’s life story to take the reader on a deep probe into his thoughts, emotions, and actions as he initially flees a very successful career in Germany when Hitler comes to power and settles in Los Angeles to escape Nazism. There, without his European reputation and status and neither speaking nor understanding English well, he is reduced to directing a movie he knows is terrible, and, as he predicted, it bombs. Kehlman provides us with an unsettling description of the situation of the emigrant, stranded, isolated, and dislocated.

In LA, Pabst is approached by a German agent with an offer that he return to the Fatherland and make great movies, but he angrily refuses. However, he is soon called to Austria to see his ailing, aged mother, and while there, he is trapped when war breaks out. Pabst, needing to work and tempted by unlimited budgets, stars, and access finally yields to the demands that he make movies for the glory of the Third Reich. Along the way he becomes aware of the Final Solution and the barbarity of the Nazis when concentration camp prisoners are used as extras in his movies. Does he sell his soul for art or take a stand against inhumanity? He chooses the former, making excuses for his compliance: “Times are always strange. Art is always out of place. Always unnecessary when it’s made. And later, when you look back, it’s the only thing that mattered.”

There is a fascinating side story in the book which follows the thoughts and actions of an English writer who is forced to attend the opening of a Pabst movie. The writer had been interned in Germany as a foreign national when war breaks out. There’s no question that this thinly disguised writer is P. G. Wodehouse, the British humorist who made broadcasts for the Third Reich while he was held there, providing another example for Kehlman to pose the question of resistance vs. compliance, a recurring description of the ‘go along, to get along’ mentality that characterized the Germans as Hitler rose to power.

The reader gets a sense of the oppressive fear that Germans lived with as the Gestapo arrested people seemingly at random. We witness two such arrests when agents enter Pabst’s house to arrest a screenwriter and also when they kidnap his Ministry of the Arts contact on the street. In both settings, nobody lifts a finger or raises a voice in protest. Silence is the practice in the face of brutality.

Kehlman tells this story with great skill. Occasionally moving into the surreal as the border between reality and dreams gets fuzzy and with two seemingly peripheral characters, Jerzabeck, the overseer of his Austrian ‘castle’ and Franzl, Pabst’s assistant director. The former, a seemingly low level, unimportant functionary, is cast by Kehlman as a major determinant of the action, from penning the telegram that brings Pabst back to Austria to some sense that he’s in some sense the power behind Hitler. When Pabst and his wife are lost deep in underground caves while making a movie, they encounter the likenss of Jerzabeck in cave paintings from thousands of years ago, indicating the inherent and perpetual evil that man is capable of. Franzl is also cast as a much more powerful player in Pabst’s life than the surface relationship would indicate appearing in both the first and final chapters both introducing and finalizing the action.

To avoid spoiler alerts, I’ll simply say that this is a terrific book. Sometimes confusing and often disconcerting, it provides a view of life in Nazi Germany from the standpoint of one artist and his attempts to live and carry on in the face of unspeakable horrors.