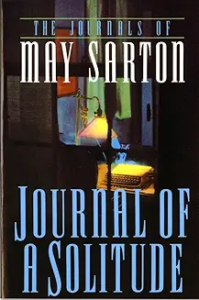

Journal of a Solitude by May Sarton 1973

I discovered this book at the CPL as part of their exhibit of Short Books for Short Days, drawn to May Sarton’s book by the title. I’ve always been fascinated by solitude, the being alone without the feeling of loneliness.

Having married at 22 while in medical school, I have never had much experience of living alone as an adult, and as such, solitude has always held a certain mysterious allure. Eleven years ago, when I was spending some time alone in Vermont, retired while my wife was still working, I read Doris Grumbach’s “Fifty Days of Solitude” written 30 years ago. That was a special book whose cover depicting a snow-covered hill led me to the artist, Donald Furst, whose colored print “Into White I” now hangs in our Cambridge home. Sarton, like Grumbach, an aging Lesbian writer living in New England, has written a sadder, more troubled account of her 60th year.

In the midst of a breakup with a longtime lover, Sarton struggles to find a comfortable way to be alone, to work on her poetry, to understand life as she moves towards old age. I didn’t enjoy the process or the format which, written as a daily journal, felt unfocused, self-absorbed, and too self-pitying. I don’t know Sarton’s poetry, but the entry about her in the Poetry Foundation includes this quote from Jane S. Bakerman who remarked in Critique that Sarton “treats in her novels (and poetry) two basic motifs from a variety of points of view, one of which is the driving need of each individual to ‘create’ himself, to come to a deep and positive kind of self-understanding which will both liberate and discipline him so that he can live in the deepest and highest reaches.” Bakerman continued: “In the process of achieving that understanding, the individual must, also, come to understand others and his relations with them. The conflict that such a search generates is always identified in Sarton’s works as the difficult and sometimes destructive thrust of each human to unite with others in friendship and love while he is dealing with an equally stronger urge to remain aloof and inward. I think Bakerman captured Sarton’s main theme, though I find it ironic that Bakerman used ‘him’ and ‘his’ throughout this observation—Sarton would have been pissed.

This description of Sarton’s work rings true, and I will search out her later book on her life in coastal Maine after she moved from her family home in Nelson, NH, not far from our route driving to Vermont from Cambridge. In addition to Nelson, there were many points of connection with Sarton—her living in Cambridge, her support of McGovern in 1972, her meeting with another favorite literary critic, Carolyn Heilbron. It may be that the major problem in my reading this book was its diary format, inevitably less organized and structured than a more traditional essay-like approach to solitude. Or it may be that I just didn’t identify enough with the issues and struggles expressed by this unhappy, lesbian poet.