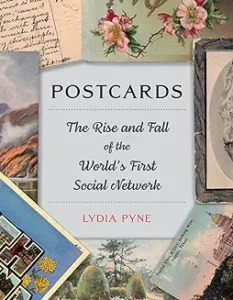

Postcards: The Rise and Fall of the World’s First Social Network by Lydia Pyne 2021

I am fascinated by postcards, and I also go to a lot of museums. Among all those museum visits over the years, one exhibit stands out above the others—the On Kawara retrospective at the Guggenheim in 2015.

I don’t think that I had ever heard of Kawara until that day, but I experienced a modified Stendahl Moment (definition from Wikipedia: a psychosomatic condition involving rapid heartbeat, fainting, confusion, and even hallucinations,[1] allegedly occurring when individuals become exposed to objects, artworks, or phenomena of great beauty.) while viewing the exhibit entitled “Silence’. I was most fascinated by his practice of sending two postcards daily to friends containing rubber stamped information about where he was writing from and what time he got up. Totally taken by this method of dealing with the paradox of the fragility, beauty, and impermanance of each day and its mundane, forgettable content, I began a daily practice of sending a postcard (or occasionally two) every day to a friend bearing the following information: the date, where I am writing from, the number of the postcard, i.e. how many I’ve written up to that time, the number of days I’ve been alive, and the time I got up that morning. I began that practice on January 1, 2016 and as of today, I’ve sent 3031 of these postcards.

I also write a postcard every Monday to each of my four grandchildren ranging in age from 2 to 9. The oldest has now recieved 508 postcards while the youngest has received only 138. The image on the front hopefully engages their visual interest while the message on the back will hopefully provide them with both a reminder of our time together and a historical record of what we did and who I was should they look at these postcards long after I’m gone.

All in all, not counting the hundreds of postcards I have been writing since 2016 to remind voters to vote in varous elections from Georgia to California, as of this morning, I’ve written 4333 postcards. You can read more about this practice at www.EpsteinReads.com/home/other-projects/.

Given all of this postcard activity, it’s easy to understand why I was drawn to Pyne’s book. Despite some serious editorial failings (‘it goes without saying’, ‘to say the least’ , and ‘comprised of” all managed to avoid the editor’s pencil!) and some mediocre writing, the book provided some interesting history and observations. The first postcard was probably sent by Theodore Hook, Esquire of Fullham outside London in 1840. By 1874, postcards were being mailed in such numbers that 22 countries signed the Treat of Bern that established rules for international mail rates and the size of the postcards. Britain passed the Private Mailing Act in 1898 to officially set the rate for postcards at one penny. By 1920 it’s estimated that 10 billion postcards were being mailed worldwide each year and nearly 700 million in the US alone. The huge growth in postcard use was responsible for bailing the US Post Office out of the red in 1905.

The popularity of the postcard paralleled the more current use of Instagram and Facebook—cheap, lightweight, a delivery system already in place, no expectation of a response. Similarly, the postcard then and social media now are easy means of making contact and connection with little effort and cost. Used for propaganda, advertising, and creating a nation’s legitimacy (this was especially true with Russia’s transformations from tsarist to Communist, from empire to imperial ambition), much of the content of postcards written in the early 1900’s would feel quite familiar on Instagram—‘having a wonderful time, wish you were here’.

A detailed bibliography left me with two impressions. First, there is a large literature about this topic featuring such nail-biting titles as “How Linen Postcards Transformed the Depression Era into a Hyperreal Dreamland” and Martin Parr’s “Boring Postcards” from 2004. Second, there’s a real interest postcards in our time even with today’s social media. As Pyne writes in her final chapter, “For over one hundred years, we have been hearing that postcards are a dying medium—and yet we continue to see them, encounter them, and know them, as we have done for decades”. Terrible writing, but a clear message that the postcard is alive and well.

I am totally engaged with my postcard practice. I love shopping for them in every city I visit, every museum gift shop we stroll through, and every airport we fly into. The choosing of the postcard, the deciding whom to send it to every day, the use of my beloved rubber stamps to fill in the information, the writing of my friend’s address, and the dropping of the card into the mail slot at the post office or in the corner mail box all reinforce my being present in the world and my message to the recipient: “I am alive. You are alive. Aren’t we just the luckiest people in the world!”