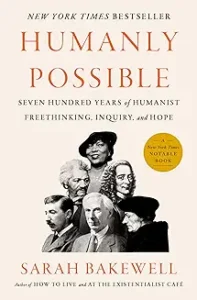

Humanly Possible: Seven Hundred Years of Humanist Freethinking, Inquiry, and Hope by Sarah Bakewell 2023

I had loved Bakewell’s first book about Montaigne, and when I saw the cover of this book, featuring faces of Zora Neale Thurston, Frederick Douglass, Jean Jacques Rousseau, E.M. Forster, Bertrand Russell, and Erasmus, I was immediately smitten. It helped that Bakewell, an independent scholar who lives in London, had garnered some of the top prizes in writing in recent years: A National Book Critics Circle Award, a New York Times Ten Best Books of 2016 and the Windham-Campbell Prize in 2018.

And what a wonderful book she has written. Huge in ambition and scope, brimming with little-known (at least to me) anecdotes, filled with mini-biographies of fascinating people both famous and little-known, and written with humor and clarity, this was a great read. A final exam on the book might have a single question: Indicate the century when the following individuals lived, their major works, and a summary of their themes. The essay question would then go on to list the ancient Greeks Terrance, Plato, and Aristotle (400 BCE), Dante, Petrarch, Bocaccio, Erasmus, and Montaigne (16th C); the third Earl of Shaftesbury. Spinoza, and Pierre Bayle (17th C); Condorcet, Rousseau, Voltaire, Diderot, Hume, Paine (18th C); J.S. Mill, Jeremy Bentham, Matthew Arnold, Wilhelm von Humboldt Darwin, Huxley (19thC.); Bertrand Russell, Robert G. Ingersoll, and Ludwik Lejzer Zamehof, the Jewish Polish linguist who invented Esperanto (20th C). Well, you get the idea.

With wit and deep knowledge, Bakewell escaped the confines of a purely linear story line to jump back and forth between centuries and countries, from writers to philosophers, from poets to mathematicians, to tell the story of how humanism has been a thread through the last 700 years of history. She also, cleverly decided not to try to narrowly define it or specifically limit it. Rather, she identifies three overarching characteristics of humanistic thought—-freethinking, inquiry, and hope— and then finds how these themes have been carried forward through centuries of contradictory influences and realpolitik—-times of war, repression, fascism, and the current religious zealotry and nationalism.

Throughout this history, what emerges in the survival of humanistic thought are the values of diversity, tolerance, respect, and morality in service to all humans in this life, not in some promised afterlife. In addition, rather than just relying on man’s innate good nature, all the humanists agree that education is the key to developing humane citizens, and while there has been debate about the best form of this education, all have agreed that it is paramount in building a humane world.

In reading this book, I was amazed that the nearly 500 pages of rather dense information sped by so quickly, and I highly recommend it to anyone with an interest in intellectual history, humanism, or mankind. I also am eager to read a biography of Bertrand Russell who struck me as the most interesting person profiled in the book.